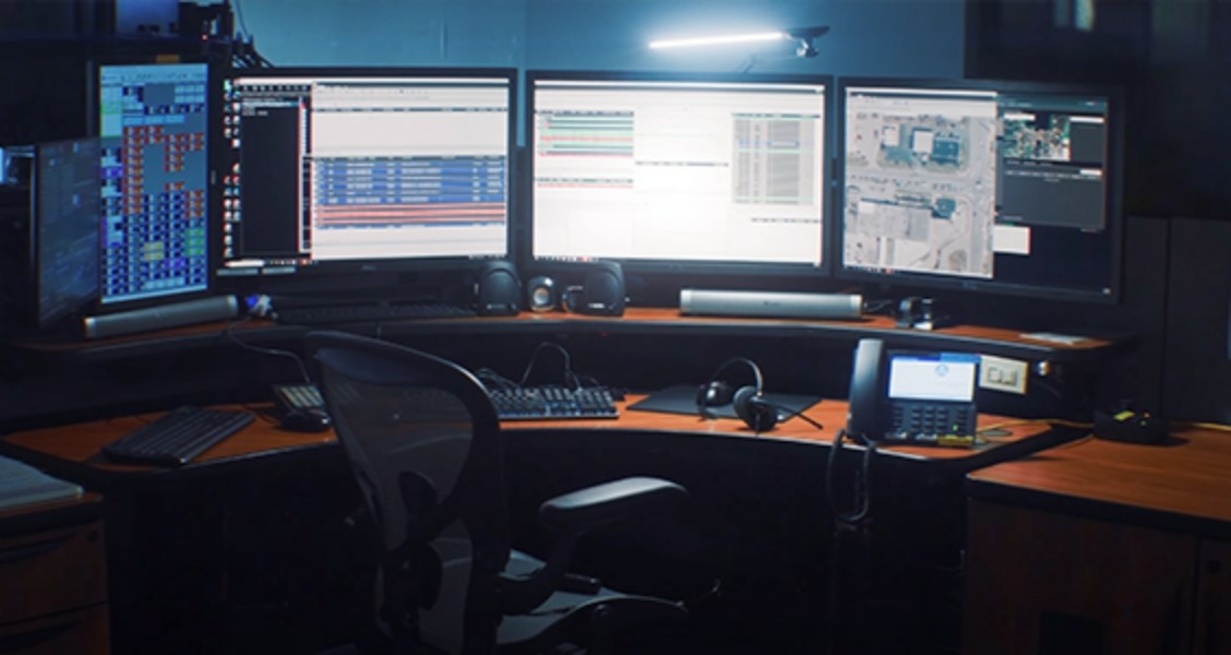

Central Dispatch Eyes Using AI for Non-Emergency Calls

By Beth Milligan | June 17, 2025

Grand Traverse County commissioners will consider a proposal Wednesday to purchase an artificial intelligence (AI) program to handle non-emergency calls at Grand Traverse County 911/Central Dispatch – potentially routing more than two-thirds of its non-911 calls to an AI agent. The move – which could free up dispatchers to focus on emergency calls – marks the first time a county staff position could be replaced with AI. County Administrator Nate Alger says more changes could be coming, though, including the potential of establishing a county department dedicated to AI.

Central Dispatch is requesting commission approval of a three-year contract with Aurelian to purchase an AI-powered call-taking system. The contract cost is $60,000 for the first year and $72,000 annually for years two and three. Central Dispatch is proposing to pay for the contract by eliminating an open full-time equivalent (FTE) position. Sixteen dispatchers work in the department now, with a few more coming on board soon. But while the staffing plan allows up to 21 dispatchers, there’s not enough room to house that many until a planned future expansion at the LaFranier campus, says Central Dispatch Director Corey LeCureux.

LeCureux says it’s a “little-known fact” that most calls taken by Central Dispatch are not 911 calls. Instead, the majority – approximately 54,500 annually – are non-emergency administrative calls. Many of those don’t require a first responder to be dispatched but are callers who ultimately need to speak to another department – whether the courts, jail, Sheriff’s Office, or sometimes completely unrelated organizations (calls about the fireworks schedule during the National Cherry Festival “happen every year,” LeCureux says).

That’s where AI comes in, according to LeCureux. The Aurelian software can serve as a routing assistant for callers who need services unrelated to Central Dispatch – redirecting them to the right department while allowing dispatchers to focus on 911 calls and radio communications. After analyzing Central Dispatch calls, Aurelian estimated that up to 67 percent of non-911 calls could be handled by an AI agent, or more than 35,000 calls annually. “This would represent 1,200 hours of time that our team would not need to be on the phone unnecessarily,” the proposal states.

Central Dispatch turns off its non-emergency lines during periods of high call volumes. Callers hear a pre-recorded message telling them to call back later. With AI, however, the caller could speak to an automated agent and potentially get their issue resolved immediately without having to call back or disrupt busy dispatchers, LeCureux says. Even when operational, the administrative line features a menu tree of options that can take 45 seconds to get through. An AI agent would be able to respond more quickly, LeCureux says.

“We want to give the community a higher level of service,” he says. “That sounds weird because we’re hiring a robot, but we think it will truly be better.” LeCureux adds that “for simple tasks of routing people, there’s no reason a human being needs to do that. People who got into this job didn’t get into it for that kind of work. They got into it for emergency calls and sending out responders.”

While handling traumatic calls can have an impact on dispatchers, LeCureux says most of their day-to-day stress stems from “the annoyance that eats away at you coming from the administrative lines, where you have entitled people who want an answer and the only agency they can get to answer the phone is Central Dispatch. So we think it’s going to be a relief for our folks.”

There are some important caveats to using AI in dispatch centers – a trend that is increasing across the nation, including in Kalamazoo and Saginaw, but is still relatively new territory. First, AI is not used to answer 911 calls. LeCureux, for all his enthusiasm about using AI administratively, doesn’t see that changing anytime soon. “When a small child calls 911, it takes a certain type of person to walk that child through the worst moment of their life,” he says. “I haven’t seen anything that will match the amazing people we have in Grand Traverse County who can walk that child through that situation.” Human interaction, situational awareness, and context clues remain vital for handling emergency calls, he says. “What makes us really good at this is our souls, and a soulless robot will never be able to accomplish that,” says LeCureux.

But what happens when someone calls a non-emergency line with what turns out to be an emergency? LeCureux estimates that happens in about 17 percent of calls. Even in non-emergencies, the types of situations people call to discuss – most commonly welfare checks, traffic accidents, trespassing, medical assistance, public disturbances, harassment, and more – can still be emotionally fraught or increase in seriousness throughout a call. LeCureux says the AI is trained to detect emotional distress and listen for certain keywords and will automatically route the caller to a human dispatcher in those situations.

A report by news outlet Source New Mexico describes AI as “quietly revolutionizing non-emergency calls in 911 dispatch centers.” Potential benefits include addressing the industry’s staffing crisis, managing call surges, and reducing dispatcher workloads. But the lack of regulation over AI and potential risks – such as programming flaws or biases that cause the AI to make critical errors or overprescribe police involvement, for example – have also made some cautious about its use. LeCureux notes the Aurelian software is “completely customizable,” so Central Dispatch can give it feedback if it does make mistakes or continually refine what calls it transfers to a human dispatcher.

Change can be difficult, LeCureux acknowledges – he anticipates there will be some initial trepidation among dispatchers about their new AI co-worker – but he believes the benefits outweigh the risks, particularly after hearing positive feedback from other Michigan communities using the technology. The contract allows Central Dispatch to terminate the program at any time during the first year and receive a pro-rated refund, LeCureux notes. He’s hopeful that if approved by commissioners, the AI program could be deployed yet this summer.

County Administrator Nate Alger says the proposal represents “the first implemented activity where a staff position would be replaced by an AI platform.” However, administrators and IT staff have discussed “embracing AI more and looking for other ways to create efficiencies using it,” he says. That could include creating an AI department led by “somebody who’s on the cutting edge of this and could identify ways to implement it in the county,” Alger says. While critics have worried AI could significantly impact the job market – particularly eliminating entry-level jobs – Alger says the county isn’t focusing on replacing its people but streamlining operations.

“I don’t think the goal is to replace law enforcement or senior center providers with AI,” he says. “It’s things like having AI listen to meetings and categorizing (the minutes) versus having someone sitting there taking notes. It frees up that staff member to do something else. You still need to have the human element.”

Comment